Freedom from Torture

Civil Society Coalition against Torture and impunity in Tajikistan

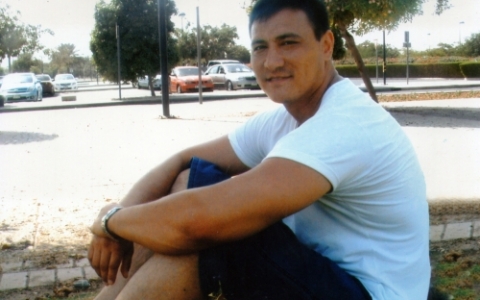

The story of 33-year old Khurshed Bobokalonov, a gifted and promising young oncologist, is not very different from many similar stories that occur during arrest or in detention. His death was as pointless as it was tragic.

It was a hot Saturday of June 27, 2009 and the country was marking the annual Day of National Reconciliation. The law enforcement officials patrolled the centre of the capital, Dushanbe. Many areas had been cordoned off and guarded because of a concert that was due to be held in he centre later that day as part of the festivities.

Khurshed, a handsome, athletic young man, left the gym carrying a sports bag. He started walking towards the carriageway of the city’s main boulevard where he planned to flag a taxi to take him home. When a policeman shouted at him rudely, Khurshed felt it was beneath him to respond to this kind of discourteous treatment. Therefore, when police officers approached him demanding, in the same rude manner, that he show them the contents of his bag, he did not comply. Before long the young man was being pushed into a police car because – as they later alleged – “he resisted the attempts of the police to test him for alcohol intoxication”. However, witnesses have said that the law enforcement officers were unable to subdue the Herculean young man and resorted to beating him with truncheons and fists. By the time the police car arrived at the police station Khurshed was dead.

The forensic medical examination concluded: “Kh. Bobokalov’s death was caused by mechanical asphyxiation as a result of blocked airways due to vomiting, as evidenced by vomit visible in the X-ray of the airways; of acute lung and heart emphysema (Tardieu’s spot); increased hyperaemia of internal organs, anaemia of the spleen and numerous marks on the body”. The examination further stated the following injuries: abrasions in the area of both shins and knee joints, on the outside of his right fist and on the left frontal and right parietal bones. The moist nature of the injuries suggests that they “were caused by blunt heavy objects shortly before the moment of death.”

A few days later, on 6 July, the Prosecutor of the Ismoili Somoni District opened a criminal investigation into “death through negligence”, a charge that carries a terms of imprisonment from two to five years. It seemed that justice was going to prevail and that the full weight of the law would come to bear on those guilty of the crime. However, two months’ later the investigating officer suspended the investigation. Khurshed’s mother and the family’s lawyer persisted until the investigation was reopened in October, but a month later the prosecutor decided to close the case “as it was not possible to identify the individuals to be held accountable for Kh. Bobokalonov’s death”.

Khurshed Bobokalonov’s family, from left to right: daughter, mother and son

Following numerous appeals to the Prosecutor General’s office, the investigation was reopened in November 2011 under the same article.

Gulchekhra Kholmatova, the lawyer representing the aggrieved party, reported that a histological analysis and a fresh forensic medical examination was carried out by independent experts two and a half years later, as part of the reopened investigation. It found discrepancies with the results of the earlier examination. It further emerged that the Kh. Bobokhalov’s blood tests had been destroyed and their results haven’t been recorded in the archives, making it impossible to determine whose blood traces had been found on the clothes Khurshed was wearing at the time of his death.

All this suggests that the original forensic medical examination was not objective and that, based on its results, the investigation had followed a wrong track, that its results had been falsified and the original conclusion was wrong to conclude that Khurshed had choked on his vomit.

The report from the forensic examination states: “… The immediate cause of Kh. S. Bobokalonov’s death was a fatal disruption of his heart’s rhythm…. The following factors had contributed to the fatal arrhythmia: intense physical exertion; psychological and emotional stress; being held for approximately 5 to 6 minutes in a confined and partly enclosed space (a virtually unventilated section of the patrol van).”

In June 2013, three years after Khurshed’s death, a reconstruction was arranged at the scene. The events of the tragic evening were reproduced: the same police van arrived and the same young people who had been with Khurshed at the time were present.

The only remaining hope was that Tajikistan’s Prosecutor General will carry out an objective assessment of the new forensic examination, reassessing all circumstances of the criminal case and, conducting an impartial investigation of Khurshed Bobokalonov’s tragic death so that the genuine cause of his death and the individuals responsible for it can be identified.

Alas… Those responsible for Khurshed’s death have yet to be identified. Nobody has been punished for the police violence and abuse. In spite of everything, several years after the life of her only son was tragically cut short, his inconsolable mother hasn’t lost hope that the case will be reopened and objectively investigated.

Saodat Kulieva, Khurshed Bobokalonov’s mother, has been running from pillar to post at the Prosecutor General’s office trying to get justice and ensure that the men she refers to as “executioners in uniform” are brought to justice. She states in one of her numerous appeals, dated April 2011: “…Not a single one of my requests to look into the criminal role played by officials of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) in my son’s death, has received a substantive response. A year and ten months have passed since the tragedy, yet not a single official has been charged with a crime or, at the very least, with deliberate abuse of power. In fact, most of the investigation has been wasted on arriving a rushed conclusions, without any implications for the MIA executioners. I have been fobbed off with standard letters; the district prosecutor’s office has been criminally inactive and has sabotaged the investigation. False witness statements have been passed off as truth. Steps were taken to cover up facts and circumstances of my son’s death.

Now Khurshed will be remembered only by photos

In my view, the job of the Prosecutor is to fight lawlessness, not to cover up infringements carried out by law enforcement officials but rather punish them with the full harshness of the law. My son's murderers, hiding behind the law and their high status, are guilty of the worst thing imaginable: of beating up and killing innocent people, undermining our faith in justice, protection of law and our belief that we live in a state of law rather than in a jungle where one has to fight for survival.”

I met Saodat Kulieva in January 2013. Her eyes are filled with unspeakable grief, devastation and tears. The following quote comes to mind: “A man who loses his wife is a widower. A woman who loses her husband is a widow. But there is no name for a parent who loses a child, for there are no words to describe this pain.”…

These days she lives in another, unreal world composed of memories of her son. Yes, that’s all she has left, memories that bring pain but also give her strength to go on living and not give up.

Saodat pulls herself together and begins telling her son’s story. “For me the year 1976 has special significance as it’s the year my son, Khurshed, was born. His coming to this world had induced a state of euphoria in all of us – his parents and close relatives. He was an exceptionally beautiful child, surrounded by affection and attention, and very bright. By the age of five Khurshed was able to read and recite by heart, from beginning to end, poems by Korney Chukovsky, Agniya Barto and other children’s writers. These days nobody bats an eyelid at seeing a ‘precocious’ pre-schooler. But back then it was quite rare. And Khurshed continued to be amazingly bright. In his early school years he was at the top of the class. I still have a paper medal he won in a contest for the cleverest child in class. His classmates unanimously voted for Khurshed. He was a member of a chess club from an early age and could beat his grandpa at chess; he played table tennis, took part in various sports competitions, played football.

Khurshed graduated from secondary school with good grades. He went on to study medicine, gaining a medical diploma. He loved his job. He would talk to me for hours about day at work had gone. He really felt for his patients and was able to talk about each of them in great detail for a whole evening and analyze the treatment. He had always been extremely open with me. I think we were great friends. I still cherish his school essay entitled “My Friend” in which he refers to me, his mother, as his best friend. Each word in this essay is precious to me.

It would be disingenuous for me to say that our life was completely unclouded, that my son had been an ideal child. Of course, there were moments when he did upset me with some thoughtless action, and sometimes we, his closest family, suffered most from things he had done. But we still loved him, nevertheless. I have kept only the memories that cheer me up. I can give you lots of examples of how much Khurshed cared about me and about his nearest and dearest. He made sure I didn’t exert myself physically, cleaning or getting food from the market. He would rush to me with injections and medication whenever I was poorly.

What I found especially moving was that he had never forgotten my. Each year, first thing in the morning, he would bring me as many of roses as the number of my years. His 55 roses were the last…

At weekends he couldn’t imagine not going to see his girlfriend who lives in a suburb. All these tokens of affection are very precious to me.

I will never forgive my heart for not feeling the pain my child went through just five minutes’ away from my home. I reproach myself for having brought up my son to be proud, not to bow his head to anyone if he hasn’t done anything wrong. Servility was alien to him, and he has paid with his life for his insubordination.

But perhaps, in spite of my love for Khurshed, I had demanded too much of him in my effort to bring him up as a real man. I had always longed to protect him from something. The way it worked in our house was that he always would tell me where he was going, when he would be coming back, even before going to the operating theatre he would let me know how long the surgery would take.

I know that when I talk about Khurshed it’s all a bit muddled but I think my state of mind is understandable. It’s hard for a mother to speak of her son in the past tense. To raise a son, an extraordinarily gifted professional, to bring him up in the best family tradition, a patriot of his country, a caring and loving family member, and to lose him to the lawlessness that reigns in our country, the corruption of the powers-that-be, that’s impossible to come to terms with.

I live on thinking that the sun rises and sets, rain follows after snow, people around me hurry and bustle about, children laugh. Everything is as usual… It’s as if nothing has changed in this world, yet my Khurshed is no longer part of it. He isn’t and will never be. He will never come, he will never hug me and he will never say the word: “Mum…” And I, his wretched mother, am alive and haven’t even lost my mind, except that my life has lost all its meaning. And my home, which he loved to visit so much, which used to offer him a peaceful shelter from everyday problems, this home has simply ceased to exist. I am slowly dying of grief, and I am dying doubly because I have to go through this on my own.

Now, that my son has died a tragic death, I shall never be able to hold him in my arms, caress his head, say loving and affectionate words to him. I had often felt like doing that in his lifetime but I used to put on a strict face and talk to him as a completely grown-up man, always telling him what’s right and what’s wrong. I thought we had so much time ahead of us. My son had accepted these rules of our relationship and listened to me. I know my son understood that his mum loved him very much and wanted only the best for him. Particularly in the last few years Khurshed matured, and my soul rejoiced at seeing him turn into a decent human being, and although I wanted to praise him more often, yet again, I didn’t want to overdo it and was sparing with praise.

Dear Lord! If in his lifetime it had ever occurred to me, even for a moment, that I might lose him!... We often get upset about daily squabbles. Please don’t forget that your children are alive and well, that they need your love and understanding and you will understand how insignificant everything else is…

This tremendous grief has now helped me understand genuine human qualities and I would like to tell everyone who reads this: love your nearest and dearest every minute of your life.

On 27 June 2009 the life of my only child was tragically cut short. It was the blackest day, which has erased my entire life. Three years have now passed since I lost Khurshed. He was a nice, kind boy but his earthly life turned out to be too short. It’s as if he had gone, closing the door behind him, leaving me all by myself, with all the words I hadn’t said. He loved life, he loved us and wanted to be happy.

Khurshed has been laid to rest at the cemetery where my mother is buried. Thank God she never had to learn in what circumstances her beloved grandson has died. I often come here and feel his presence next to me, and that gives me strength to go on living, not for my sake but for the sake of his young children. The tragedy occurred on a Saturday and every Saturday when I come to see him, I say: “See you soon, my son, see you where there is no pain and evil. Khurshed, we shall meet again in the best of all worlds, you have gone ahead before me, it was your fate to meet us all there – those of us who have buried you and those who killed you. I very much hope that the hands of those who killed you are stained with blood, and they won’t be able to wash it away. I can’t stand Saturdays now.

Khurshed managed to achieve a lot in his short life. He has left a nice memory in many people's hearts. His children – son Dier, a spitting image of Khurshed, and daughter Dinora – are growing up and they can always be proud of their father. Whenever I come into contact with anything that relate to Khurshed even in the most indirect way, I see the lovely image of my son – the baby, the school boy, the student, Dier's and Dinora's father – so close and yet so distant.

After burying my son (the funeral took place at his place of birth) I wasn't able to go back home for forty days. I decided straight away that the minute I returned I had see the image that is so dear to me. I asked my colleagues at work to have a huge, ceiling to floor portrait made of Khurshed, smiling, which should wait for me when I arrived. His photographs are on the walls and on display all around my flat. Now he is with me forever and I can see him all the time. I have kept his things ,which still smell of him. He is alive not only in every corner of my soul but in very corner of my home. Every time I cross the threshold of my home I immerse myself in endless memories of him.

In Islam, like in many other world religions, it is customary to visit the graves. Every time you come to a cemetery as a living person you try to comprehend the fact that death is inevitable for each and every one of us. Of course, Khurshed was perfectly aware of this and had accepted the transience of his existence in this “temporary world”. That is probably why he was so recklessly courageous and terrifyingly just in the last minutes of his life, as he was confronted by blatant abuse of power, not ordinary abuse but a lawless abuse committed by an organized criminal group of state officials.

Browsing through the pages of his biography, I think that the most striking an tragic page shows the last minutes of his life, when the executioners in uniform were unable to break my son’s will and force him to his knees in front of hundreds of onlookers.

I believe that, whatever the Almighty has decreed, it is WRONG for a grandfather to bury his grandson, for a mother to bury her son. I feel like shouting: it is WRONG to kill someone for insubordination.”

A criminal investigation into the death of Khurshed Bobokalonov was initiated on 6 July 2009 and has not yet been completed. Despite the persistent efforts of his mother and the lawyers to identify what exactly happened and who is responsible for his death nothing is clear yet. The investigation was closed and reopened for several times. His mother realized that the authorities persistently refuse to take any steps to identify the perpetrators or cooperate with her, not providing information about the investigation and failing to response to lawyer’s letters. To the date, no one has been held accountable for the death of Khurshed Bobokalonov.

Materials was prepared in the frame of the project on “Actions against torture in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan”, with financial assistance of the European Union The contents of this materials are the sole responsibility of the organizations issuing it and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.

Materials was prepared in the frame of the project on “Actions against torture in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan”, with financial assistance of the European Union The contents of this materials are the sole responsibility of the organizations issuing it and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.